[HWASA] 'Good Goodbye' MV Explained: The Art of Letting Go with Dignity

I need to be honest about something: I've watched this music video over thirty times in the past week, and I'm still finding new details to unpack. HWASA's "Good Goodbye" isn't just a breakup song—it's a masterclass in how to end something beautifully. And with Park Jeong-min bringing an acting performance that rivals his filmography, this might be the most mature love story K-pop has told all year.

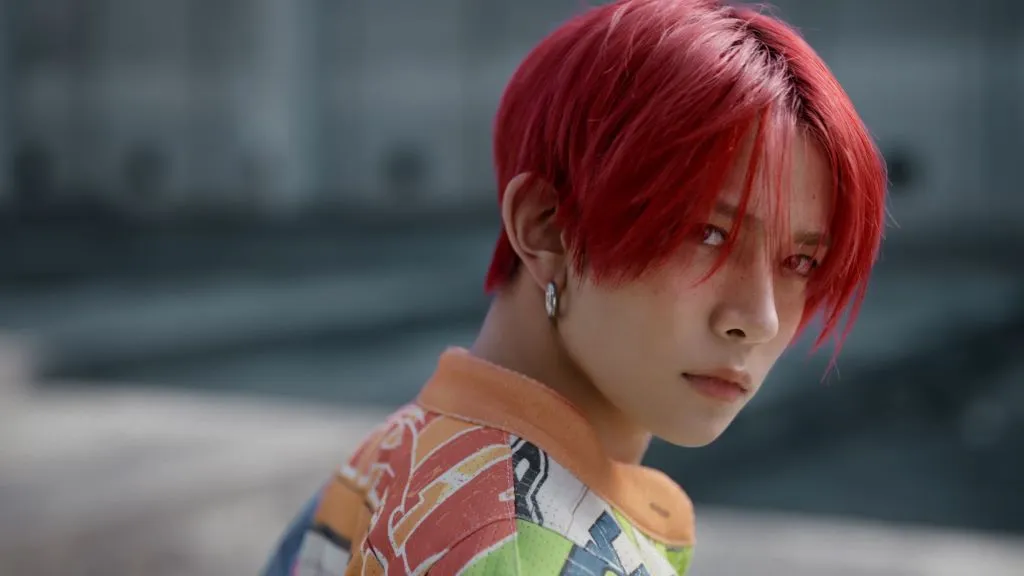

Source: Official P NATION YouTube (© P NATION)

Table of Contents (Find Your Story)

Quick Summary: The Vibe Check

Let me start with what struck me first: the refusal to be sad.

“Good Goodbye” operates in a space most K-pop breakup songs avoid—the recognition that some endings, however painful, are necessary acts of self-preservation. HWASA isn’t crying into her pillow. She’s not begging anyone to stay. Instead, she’s standing on a windswept beach, dressed in red, literally embodying the act of moving forward.

The song pairs upbeat, almost celebratory instrumentation with lyrics about heartbreak, creating a cognitive dissonance that mirrors the complicated emotions of healthy separation. You’re not supposed to feel just sad or just relieved—you’re supposed to feel both simultaneously, which is exactly how real endings work.

Park Jeong-min’s presence elevates this from music video to short film. His performance brings a grounded realism that’s rare in K-pop visual storytelling. He’s not playing a character; he’s playing someone who exists, who loves, who’s flawed, who’s trying. The chemistry between them feels lived-in, like we’re watching the final chapter of a story that’s been unfolding for years.

The cinematography choices—film grain, natural lighting, handheld camera movements—deliberately evoke analog photography and home videos. This isn’t polished idol content. It’s memory, preserved.

Credits

The Story You See on Screen

The Opening: Wounds and Acceptance

The music video begins with HWASA’s hands marked by visible scratches and wounds. It’s a visual metaphor that’s simultaneously literal and symbolic—these are the marks left by love, by holding on too tight, by the friction of trying to make something work that was always going to end.

Park Jeong-min enters the frame not as a romantic ideal but as a real person: rumpled, imperfect, visibly frustrated. The genius of his casting becomes immediately apparent—he brings an everyman quality that grounds the entire narrative. This isn’t a fantasy boyfriend from a drama; this is someone who could be your ex.

The Island as Liminal Space

The choice to set this story on what appears to be an isolated island is deliberate. Islands exist between departure and arrival, between land and sea, between one life and another. It’s where you go when you need to be separate from the world to figure things out—or to end things properly.

The couple moves through scenes that feel like the greatest hits of a relationship: dancing together in matching outfits, sharing meals, playful moments on the beach. But there’s a melancholy undertone to everything. These aren’t new memories being made; these are old memories being honored before they’re filed away.

The Visual Language of Distance and Closeness

Watch how the camera work shifts throughout the video. Early scenes show them in the same frame but with increasing physical distance—sitting on opposite ends of a table, walking separately, turning away from each other. Later, as they accept the ending, they actually get closer: dancing in sync, embracing in the rain, foreheads touching.

It’s a counterintuitive progression that reveals something profound: sometimes you can only be truly close to someone once you’ve both accepted that you’re leaving. The pressure is off. You can be honest now.

Park Jeong-min’s Micro-Expressions

At 1:49, there’s a moment where Park Jeong-min sweeps HWASA’s hair back from her face while looking simultaneously tender and resigned. It’s an actor working at the top of his craft—conveying years of intimacy and imminent loss in a single gesture. These are the moments that make people in the comments section say they’re watching a film, not a music video.

The rain scene at 2:12 showcases another layer. As HWASA dances playfully, Park Jeong-min shields her mouth from the rain with his hand—a protective gesture that’s both loving and futile. You can’t protect someone from life. You can only be present for moments like these.

The Book as Shield (3:26)

At 3:26, we see one of the video’s most tender moments: Park Jeong-min holds a book over HWASA’s head as makeshift shelter from the rain while she dances beneath it. It’s a gesture that encapsulates the entire relationship—his instinct to protect her, her need to move freely, and the fundamental impossibility of doing both simultaneously.

The book is significant. Not an umbrella, not his jacket—a book. Something meant to contain stories, to preserve narratives. He’s literally trying to shield her with story, with memory, with the relationship they’ve written together. But books get ruined by rain. Stories can’t protect you from weather, from life, from the inevitable.

And HWASA keeps dancing. Not because she’s ungrateful for the gesture, but because her body needs to move through this. You can’t dance and stay dry. You can’t live fully and remain protected. The scene visualizes the core incompatibility: he wants to keep her safe; she needs to be free.

Locking Away the Memories (3:29)

The video’s final symbolic gesture occurs at 3:29: HWASA closes and locks a box. We don’t see what’s inside, but we don’t need to. We’ve just watched nearly four minutes of memories being catalogued, honored, and prepared for storage.

This isn’t destruction—she’s not burning photographs or throwing away mementos. She’s preserving them, but making them inaccessible. The lock represents a conscious decision: these memories happened, they matter, and now they need to be sealed away so she can move forward without constantly reopening old wounds.

There’s something deeply mature about this choice. Not erasing the past, not pretending it didn’t happen, but choosing when and how to access it. The lock gives her control over her own narrative. She decides when to remember, rather than being ambushed by memory.

The Red Dress as Statement

HWASA appears in two primary looks: casual, natural styling during the “relationship” scenes, and a striking red dress in the “aftermath” moments. Red is confrontational, bold, alive. It’s the color of someone who’s choosing to feel everything rather than numb out.

The styling choice of her short hair and sun-kissed skin continues the aesthetic established in her recent work—this is HWASA fully inhabiting her own vision, unconcerned with conventional K-pop beauty standards.

The Ending: Literally Walking Away

The final sequences show them literally turning away from each other and walking in opposite directions. No dramatic confrontation. No last-minute reunion. Just two people who loved each other, acknowledging that love wasn’t enough, and choosing to remember it well.

The last shots of HWASA alone, moving forward, capture something essential: she’s sad, but she’s not diminished. The ending didn’t break her. If anything, she seems more solid, more herself.

Lyrics & Meaning

“Just Step on Me and Go”

The opening lines are startling in their directness: “나를 그냥 짓밟고 가 / 괜찮아 돌아보지 마” (Just step on me and go / It’s okay, don’t look back). This isn’t masochism—it’s permission. HWASA is releasing the other person from the burden of guilt, from the need to check if she’s okay, from the trap of mutual destruction.

“내가 아파봤자 너만 하겠니” (Even if I hurt, would it be as much as you?) acknowledges a fundamental imbalance. One person always hurts more. One person always wanted it to work a little harder. And HWASA is saying: I know that person is me, and I’m handling it.

“Kill My Ego”

“날 위해 쉬던 그 숨은 잊고 / 저 위에 널 위해 just kill my ego” (Forget the breath you took for me / Just kill my ego for you up there) is the song’s emotional pivot point. She’s consciously choosing to let go of pride, of the need to be right, of the ego’s demand that relationships end badly if they end at all.

This is the move of someone emotionally mature enough to distinguish between self-respect (which she maintains) and ego (which she’s willing to sacrifice). The instruction to “크게 웃어줘” (laugh loudly) reinforces this—she wants the other person to thrive, even if their thriving doesn’t include her.

The Chorus: “Good Goodbye”

“안녕은 우릴 아프게 하지만 우아할 거야” (Goodbye will hurt us, but it will be elegant) is the thesis statement. The Korean word “우아하다” (elegant/graceful) is fascinating here—it implies dignity, poise, beauty even in difficulty. This isn’t about pretending it doesn’t hurt. It’s about hurting beautifully.

The repeated “goodb-ye” (굿바이) playfully breaks the English word “goodbye” while keeping its meaning, suggesting a “good” version of leaving—one that doesn’t destroy what was built.

“I’ll Be on My Side Instead of You”

The bridge introduces the song’s most powerful assertion: “세상이 나를 빤히 내려다봐도 / 내 편이 돼줄 사람 하나 없어도 / Don’t worry it’s okay / 난 내 곁에 있을게” (Even if the world stares down at me / Even if there’s no one on my side / Don’t worry it’s okay / I’ll be by my side).

This is the lyrical moment that makes grown adults cry in comment sections. HWASA articulates something revolutionary: self-partnership as the ultimate safety net. When you can be on your own side, you can survive any ending. You become unbreakable not through independence from others, but through allegiance to yourself.

The Final Goodbye to Regret

“후회조차도 goodb-ye” (Even to regret, goodbye) closes the song by releasing not just the person but the emotional aftermath. She’s not going to second-guess herself. She’s not going to endlessly replay what could have been different. Even the regret gets a good goodbye.

The Visual Punctuation: Sealing the Story

While the lyrics end with releasing even regret, the visual narrative provides a concrete image of closure: the locked box at 3:29. This final gesture connects directly to the lyrical theme of “good goodbye”—the box represents careful preservation rather than angry destruction.

In Korean culture, the concept of “정리” (jeongni—organizing, tidying up, putting things in order) applies not just to physical spaces but to emotional ones. HWASA literally performs jeongni with her memories, organizing them into something contained and manageable. The lock isn’t about denial; it’s about boundary-setting with your own past.

This visual choice reinforces what makes the song’s approach to heartbreak distinctive: it’s organized, intentional, respectful. Even the ending is choreographed thoughtfully. The locked box becomes the visual equivalent of “후회조차도 goodb-ye”—even the memories, even the what-ifs, even the urge to keep picking at this wound: goodbye.

Beneath the Surface: A Multi-Layered Analysis

The Return of Korean Lyricism in K-Pop

One of the most striking aspects of “Good Goodbye” is its commitment to Korean-language storytelling in an industry increasingly dominated by English phrases and mixed-language hooks. The song contains substantial, meaningful Korean lyrics that convey complex emotional narratives.

This matters because it signals something about HWASA’s artistic priorities. She’s not chasing global virality through TikTok-friendly English hooks. She’s crafting poetry for listeners who will sit with the words, who will translate them carefully, who will feel the weight of phrases like “우아할 거야” in their original language.

The choice reflects confidence—confidence that the song’s quality will transcend language barriers, confidence that her existing audience will appreciate the depth, confidence that emotional truth communicates regardless of whether every listener understands every word.

Park Jeong-min: The Actor Who Changes Everything

The decision to cast Park Jeong-min, one of Korea’s most respected film actors, fundamentally alters what this music video can be. He’s known for bringing psychological complexity to his roles, for making characters feel dimensional even in limited screen time.

His presence does several things simultaneously:

First, it lends cinematic credibility. When an actor of his caliber agrees to appear in a music video, he’s implicitly vouching for the project’s artistic seriousness. This isn’t a favor to an idol; it’s a collaboration between artists.

Second, his acting style—naturalistic, understated, emotionally available—forces the video into realism. You can’t have exaggerated K-pop performance styles next to Park Jeong-min’s grounded work. HWASA has to match his energy, which results in her most restrained, human performance to date.

Third, the age dynamic matters. Park Jeong-min is 37; HWASA is 29. The video presents a relationship between adults who’ve lived, who’ve had other relationships, who understand that love alone doesn’t make a partnership work. This isn’t a teenage romance—it’s a mature heartbreak, which is rarer in K-pop visual storytelling.

The Cinematography of Memory

Director Park Woo-sang made specific technical choices that create the video’s distinctive aesthetic. The apparent use of film (or convincing film-like grading) gives everything a textured, analog quality. Digital video can feel immediate and present; film feels like memory.

The handheld camera work in certain scenes introduces a documentary quality—we’re not watching a performance, we’re witnessing something real being captured. The shaky frames, the slightly off-center compositions, the natural lighting that creates harsh shadows and blown-out highlights: these are the visual markers of authenticity.

Color grading emphasizes warm, slightly faded tones—the palette of old photographs, of memories that have softened with time. Even the bright red of HWASA’s dress is a warm red, not a cool one. Everything feels sun-soaked, wind-worn, already nostalgic even as we’re watching it.

The Choreography of Disconnection

The movement in this video deserves specific attention because it’s so unusual for K-pop. There’s no formal choreography in the traditional sense—no formation changes, no synchronized group dance. Instead, there’s what I’d call “movement language”: the way the couple interacts physically tells the story as much as the lyrics do.

Watch the progression: early scenes show them moving in opposite rhythms, occupying the same space but not quite connecting. Middle sections feature moments of synchronization—dancing together at 2:21, moving in tandem—that feel like callbacks to when they were aligned. Final scenes return to separation, but this time it’s intentional, mutual, accepted.

The rain dance at 2:19 is particularly significant. HWASA moves freely, almost childishly, while Park Jeong-min remains more restrained. It visualizes a fundamental incompatibility: one person wants to dance in the rain; the other wants to shield them from it. Both impulses come from love, but they can’t coexist sustainably.

The book-as-shelter moment at 3:26 adds another layer to this movement language. Park Jeong-min creates a small dry space for HWASA using a book, and she dances within that limited protection. It’s beautiful and sad simultaneously—he’s trying to give her freedom within safety, but those two things are fundamentally at odds. The constraint of staying under the book’s coverage restricts the very freedom the dancing represents.

This physical dynamic mirrors countless relationship negotiations: How do I support you without controlling you? How do I protect you without limiting you? The answer the video suggests is: sometimes you can’t. Sometimes loving someone means accepting that you can’t shield them from everything, and they can’t stay sheltered and still be fully themselves.

The Island Metaphor: Isolation and Transition

Setting this narrative on an island does specific metaphorical work. Islands are liminal spaces—neither fully land nor sea, neither completely connected nor entirely separate. They’re where you go for transition, for transformation, for endings that need to happen away from the watching world.

The couple’s “last trip” to this island mirrors a real-world phenomenon: the breakup vacation, where couples who know it’s ending take one final journey together to honor what was before officially closing the chapter. It’s a practice that requires emotional maturity—the ability to hold “this is ending” and “this was valuable” simultaneously.

The island also functions as emotional quarantine. Whatever happens there stays there. The fights, the reconciliations, the final goodbye—they all occur in a space separate from regular life, which perhaps makes them easier to process and eventually leave behind.

Fashion as Narrative Device

HWASA’s styling throughout the video works as storytelling shorthand. The casual, comfortable clothing in “relationship” scenes—loose pants, simple tops, natural hair—suggests intimacy and comfort. This is how you dress around someone who’s seen you at your worst.

The red dress in “aftermath” scenes signals transformation. It’s fitted, intentional, striking—the outfit of someone who’s stepped back into their public self, their “I’m fine” self, their moving-forward self. The transition from casual to polished mirrors the emotional journey from raw hurt to processed acceptance.

Her short hair and sun-kissed skin continue an aesthetic HWASA has been cultivating throughout 2025—a rejection of K-pop’s traditional beauty standards in favor of something more individualistic. In “Good Goodbye,” it reads as confidence: someone who looks how they want to look, regardless of whether it fits industry norms.

The Power of Korean Emotional Expression

There’s a particular quality to how Korean language and culture handle heartbreak that “Good Goodbye” captures perfectly. The concept of “한” (han)—a complex emotion mixing sorrow, regret, and resilient hope—permeates the song without being explicitly named.

Western breakup songs often lean heavily into either anger or sadness. K-pop ballads frequently embrace melodramatic grief. “Good Goodbye” does something more nuanced: it acknowledges pain while refusing to be consumed by it. The upbeat instrumentation isn’t denial; it’s determination.

The phrase “우아할 거야” (it will be elegant) carries cultural weight. In Korean contexts, maintaining dignity and composure through difficulty is deeply valued. HWASA isn’t just saying she’ll survive the breakup—she’s saying she’ll do it with grace, which is a specific kind of strength.

Why This Resonates Across Age Groups

Comment sections reveal an unusual age distribution for a K-pop release. While HWASA’s existing fans engage enthusiastically, there’s significant response from older listeners—people in their 30s, 40s, even 50s—who rarely comment on K-pop content.

What’s connecting across generations? The honest portrayal of mature heartbreak. “Good Goodbye” doesn’t traffic in the dramatic extremes of young love—no one’s life is ending, no one’s saying they can’t go on. Instead, it shows two people who care about each other, recognizing that care isn’t sufficient reason to stay.

This is the heartbreak of adults: measured, self-aware, complicated. It’s the realization that you can love someone and still need to leave. That ending a relationship doesn’t require anyone to be a villain. That sometimes the most loving thing you can do is let go cleanly.

Older listeners see their own experiences reflected—relationships that ended not in explosions but in quiet mutual acknowledgment that it wasn’t working. Younger listeners see a model for how to handle future heartbreaks with dignity. Both groups find it refreshing.

Fan Takeaways

“Good Goodbye” offers fans a gift that K-pop rarely provides: permission to feel complicated emotions.

For listeners currently in struggling relationships, the song validates the possibility of loving someone and still needing to leave. It removes shame from the act of prioritizing your own wellbeing. HWASA models how to end something with grace rather than destruction, offering a blueprint for those who need it.

For those healing from past breakups, the song provides reframing. Maybe your ending wasn’t a failure. Maybe it was necessary. Maybe both people can be good people and still not be good together. The song gently suggests that not all heartbreak needs to be bitter—some can be bittersweet, tinged with gratitude for what was even as you acknowledge it couldn’t continue.

What fans ultimately take away is self-partnership as the ultimate safety net. The bridge’s assertion “I’ll be on my side instead of you” becomes a mantra, a reminder that your own support matters most. When you can comfort yourself, advocate for yourself, be proud of yourself, you can survive any ending.

There’s also deep appreciation for HWASA’s artistic maturity. She’s no longer proving she can be sexy or controversial. She’s simply being human, being real, being someone who’s lived enough to have complicated feelings about complicated situations. Fans respect that evolution.

Frequently Asked Questions (Q&A)

Is "Good Goodbye" about a real relationship?

HWASA hasn't confirmed whether the song draws from personal experience, and that ambiguity is likely intentional. As co-writer, she clearly invested personal emotion into the lyrics—the specificity of phrases like "I'll be on my side instead of you" suggests lived experience. However, the song's power lies in its universality. Whether it's autobiographical or empathetically imagined, it resonates because it captures something true about how mature heartbreak actually feels.

Why cast Park Jeong-min specifically?

Park Jeong-min brings several crucial elements: acting credibility that elevates the video to film quality, naturalistic performance style that forces authenticity from everyone around him, and an everyman quality that makes the story feel real rather than fantastical. He's known for portraying complex, flawed characters with empathy. In "Good Goodbye," he plays someone who's loved and failed and is trying to do the ending right—exactly the kind of nuanced role he excels at. His presence signals that this isn't typical K-pop content; it's serious emotional storytelling.

What makes this different from typical K-pop breakup songs?

Most K-pop breakup songs embrace one extreme: devastating sadness or angry defiance. "Good Goodbye" operates in the nuanced middle space—acknowledging pain while maintaining dignity, recognizing incompatibility while honoring what was good. The upbeat instrumentation paired with melancholy lyrics creates cognitive dissonance that mirrors real heartbreak's complexity. Additionally, the extensive Korean lyricism, film-like MV production, and mature emotional perspective set it apart from the more dramatic or superficial treatments of heartbreak common in the genre.

Why are older listeners resonating with this song?

The song portrays adult heartbreak—the kind where both people are fundamentally decent, where love exists but isn't enough, where the ending requires no villain. This resonates with people who've lived through relationships that ended not in explosions but in quiet, mutual acknowledgment of incompatibility. The emotional maturity displayed—prioritizing self-preservation without cruelty, releasing someone with grace, finding strength in self-partnership—reflects experiences that come with age. Younger fans see a model for future heartbreaks; older fans see validation of past ones.

What does "우아할 거야" (it will be elegant) really mean?

"우아하다" carries connotations of grace, dignity, and beauty even in difficulty. In this context, HWASA isn't saying the goodbye won't hurt—she's saying she'll handle the hurt beautifully. It's a commitment to maintaining composure and self-respect through pain, which is culturally valued in Korean contexts. The phrase suggests that how you end something matters as much as the ending itself. You can fall apart privately and still conduct yourself gracefully publicly. It's strength expressed through restraint rather than through anger.

What's the significance of the locked box at 3:29?

The locked box represents "정리" (jeongni)—the Korean concept of organizing and putting things in order, applied to emotional spaces. HWASA isn't destroying her memories; she's preserving them while making them inaccessible for daily reopening. The lock gives her control over her own narrative—she decides when to remember rather than being ambushed by memory. It's a mature choice: acknowledging the past's value while setting boundaries with it. The box becomes the visual embodiment of "good goodbye"—careful, respectful closure rather than angry destruction.

Sources & Technical Data

Credible Sources

- HWASA (화사) 'Good Goodbye' Official MV

- Soompi: HWASA Shares Emotional "Good Goodbye" MV

- YouTube comments section analysis (verified viewer reactions)

Special Thanks

To the viewers who shared their own heartbreak stories in the comments, turning the video’s comment section into a collective healing space. To those who noted the film-like quality, the mature emotional handling, and the power of self-partnership—your observations shaped this analysis. Special recognition to the person who wrote about listening to this while commuting 3 hours daily, finding solace in the song’s message. That’s the power of art: it meets you where you are and reminds you that you’re not alone.

Comments